Token‑Efficient Agents: Building MCP‑Heavy Agents Without Burning Tokens

Overview of how AI agents use MCP Tools to interact with the real world and latest mechanisms currently offered by Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google to reduce token use when using MCP with Agents.

Introduction

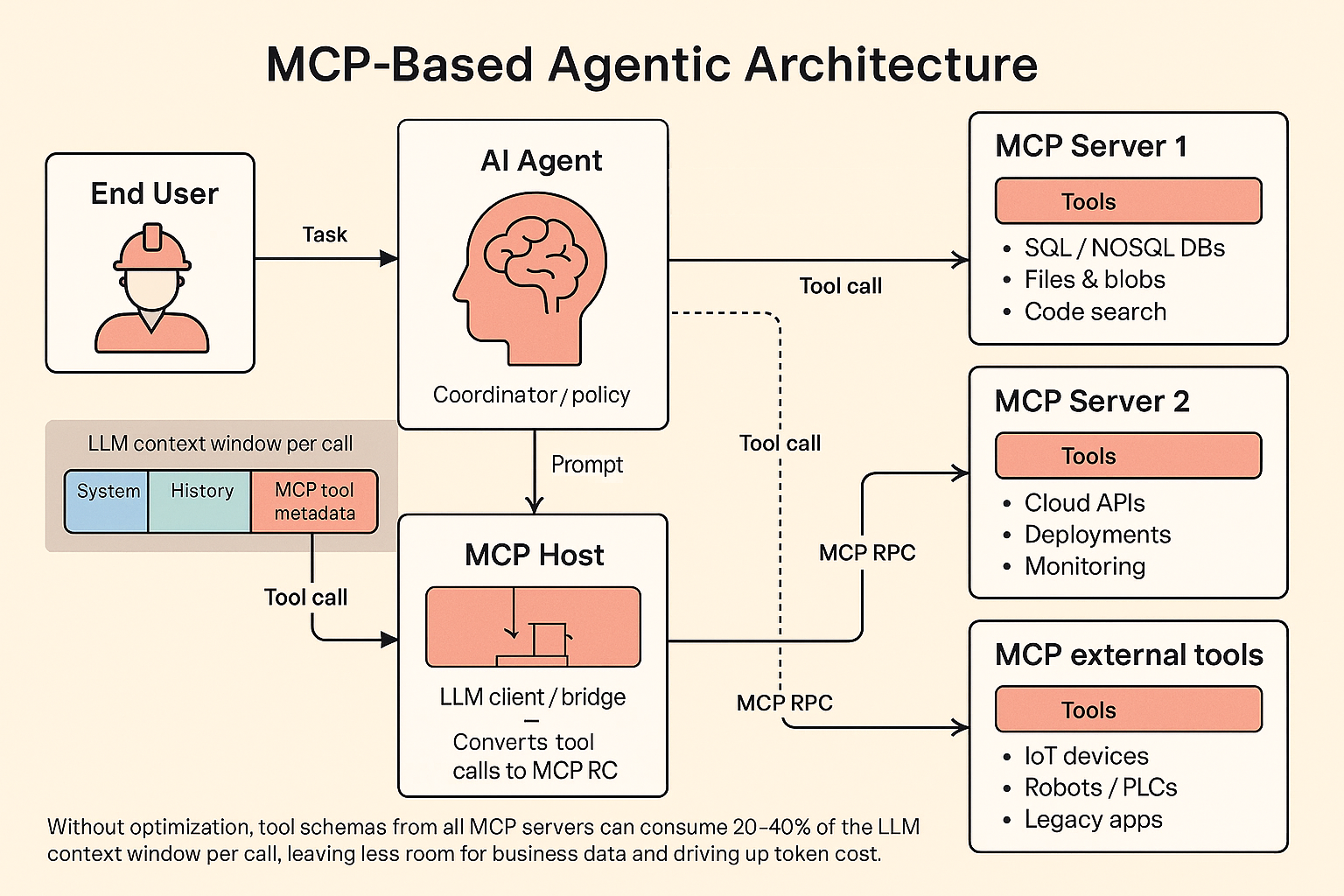

Agents powered by large language models (LLMs) and Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools are rapidly moving from demos to production systems. The main reason is simple: once an LLM can call tools that talk to your proprietary systems, it stops being “just a chatbot” and starts acting like a real worker that can read data, update records, trigger workflows, and close the loop on business tasks.

The friction starts when these systems grow beyond a handful of tools and toy use cases. As you add more MCP servers and expose more tools across more workflows, the variety of tasks you expect the LLM to handle explodes, and with it the amount of tool metadata that has to be carried in the model’s context window for every call.

If you configure an LLM client (the MCP “host”) with many MCP servers, each exposing dozens of tools, you can easily end up spending 20–40+% of your context window just listing tools and their schemas. In practice this means you are paying real money for tokens that never change and that the model rarely needs, while at the same time squeezing out the space you would rather dedicate to your actual business data. Anthropic has estimated that in some setups roughly 40% of overall token usage is consumed by MCP metadata alone. In a world where tokens are effectively the new AI “currency,” this is not just an engineering detail; it is a line item on your P&L and a lever for optimization.

This article looks at that problem specifically through the lens of MCP-based tools and agentic systems. It explains why naïve tool integration wastes tokens and degrades quality, and then walks through how Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google/Gemini address this, with a focus on Anthropic’s newer approaches to MCP usage. The goal is to give startup founders, technical leaders, and investors a clear picture of what is possible today, where the platforms differ, and how to think about architecture decisions that keep both costs and error rates under control.

- Token waste: A significant fraction of tokens are spent on static MCP metadata and verbose tool outputs that are not strictly needed for reasoning.

- Context dilution: Tool definitions and intermediate blobs crowd out business data you would rather give the model (documents, code, customer history).

- Higher cost and latency: More tokens mean higher bills and slower responses, especially when many tool calls fan out over large datasets.

Background: MCP and Agentic Systems

MCP in practice

For readers who are new to it, Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a standard way to give AI agents access to external tools, so they can perform work directly rather than only converse with users.

- An API that allows LLMs and AI agents to do something useful in the real world

- The documentation an LLM needs to understand how to use it

MCP has gained traction throughout 2025 because it dramatically expands what agents can do while keeping the integration model consistent across tools and vendors.

An MCP server is conceptually an API server, reachable via RPC, that exposes a set of “tools.” Each tool is essentially a remote procedure call: LLMs decide which tools to call and Agents execute the calls with parameters generated by LLMs and return responses back to LLM.

Typical tools might be “list files and directories on my laptop,” “add a meeting to my calendar,” or “search source code for a text pattern.” Modern LLMs are trained to emit a special tool-calling format whenever they decide it would help to invoke one of these tools. The host application watches for those tool calls, executes them against the MCP server, and feeds the results back into the model so it can continue the task.

From the LLM’s point of view, tools are just another part of its context. From your point of view, tools are how the model reaches into real systems and takes action.

Agents and workflows

“Agent” is an overloaded term. Some organizations use it to describe highly autonomous systems that run for long periods, managing complex tasks with minimal supervision. Others use it for much more constrained, workflow-like systems that rely on LLMs but stay within tightly defined paths.

Anthropic uses “agentic systems” as an umbrella term, but draws an architectural distinction:

-

Workflows are systems where LLMs and tools are orchestrated through pre-defined code paths. Control lives primarily in your application logic.

-

Agents are systems where LLMs dynamically direct their own processes and tool usage, deciding how to accomplish tasks as they go.

In practice, both follow a similar life cycle. An agentic system starts from a user command or interactive conversation. Once the task is understood, the system plans a sequence of steps, then iterates: call tools, inspect results, update its plan, and repeat. At each step it needs “ground truth” from the environment—tool responses, database queries, code execution—to assess whether it is making progress. It may pause for human input at checkpoints or when it encounters ambiguous or risky decisions. The run terminates when the task is complete or when it hits explicit stopping conditions such as maximum iterations or cost limits.

Although agents can handle sophisticated tasks, their implementation is often conceptually straightforward: an LLM repeatedly calls tools based on feedback from earlier steps. The quality and cost of the system therefore depend heavily on how you design the toolset, how you describe it to the model, and how efficiently you move data in and out of the context window.

Where the Tokens Go: The Cost of MCP Tool Metadata

In a traditional setup, an LLM client (the MCP host) is configured with one or more MCP servers and all the tools those servers expose. Most clients take a simple approach: they load all tool definitions up front, map them into the model’s tool-calling syntax, and include them in every request. The model then decides, for each prompt, which tool to call, if any.

There are two main sources of token overhead in this design.

First, the tool definitions themselves. Every tool carries a name, description, and argument schema. With a handful of tools, this is negligible. With dozens or hundreds—especially across multiple MCP servers—those definitions start to eat a noticeable fraction of your context window. The model pays this cost even when a given prompt will only ever use one or two tools.

Second, the intermediate tool call results. In a classic tool-calling loop, every tool invocation is routed through the LLM. A typical pattern for a complex task might be: system prompt and tools → user request → model decides to call a tool → host executes the tool → result is fed back into the model → the model calls another tool → and so on. The full transcript, including every intermediate response, flows through the model multiple times. The model must “see” each intermediate result, even if most of the data is incidental to the final answer.

This combination creates several problems:

-

Token waste: A significant fraction of tokens are spent on static MCP metadata and verbose tool outputs that are not strictly needed for reasoning.

-

Context dilution: Tool definitions and intermediate blobs crowd out business data you would rather give the model (documents, code, customer history).

-

Higher cost and latency: More tokens mean higher bills and slower responses, especially when many tool calls fan out over large datasets.

-

Reduced reliability: As the number of tools grows, models become less accurate at picking the right one when they are all presented at once.

Anthropic’s internal measurements, for example, show that in some MCP-heavy workloads up to 40% of token usage is spent on MCP metadata alone. That is not just an implementation detail; at scale it becomes a structural inefficiency that you have to design around.

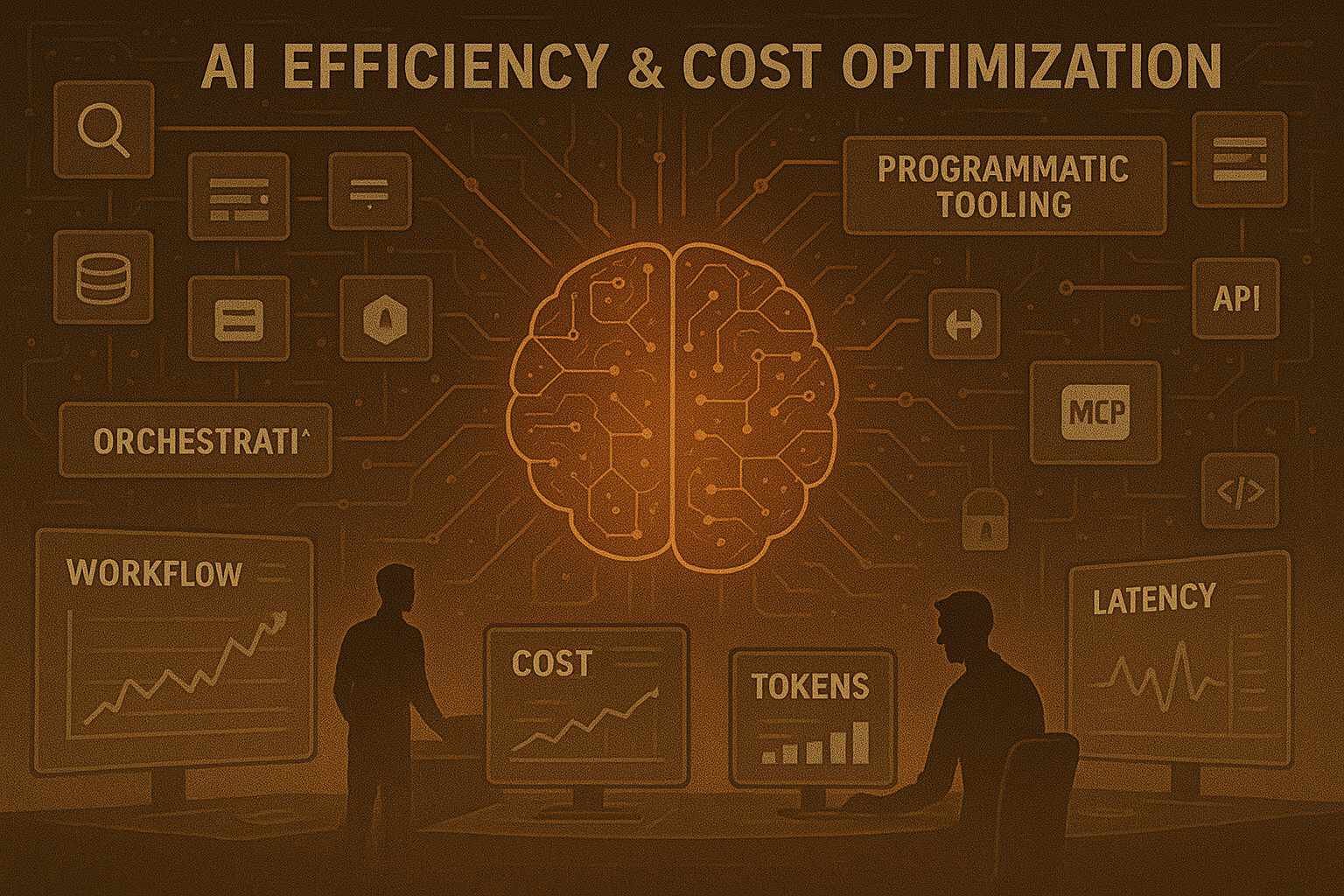

The rest of this article looks at how each of the major LLM vendors is tackling this: Anthropic with Tool Search Tool and Programmatic Tool Calling, OpenAI with Responses, hosted MCP, and the Agents SDK, and Google with Gemini, context caching, and its Agent Development Kit (ADK).

Anthropic: Advanced MCP Tool Use

Anthropic has been a key driver in the MCP ecosystem and is currently at the forefront of optimization techniques for MCP-heavy, tool-centric systems. Their recent work focuses on two complementary ideas:

-

Treating tools as a searchable index rather than a giant static list.

-

Moving orchestration out of the LLM’s context and into code that the model writes once and then hands off.

These ideas show up in two beta features: Tool Search Tool and Programmatic Tool Calling.

Tool Search Tool: tools as a searchable index

Anthropic’s Tool Search Tool addresses the problem of large tool libraries by letting Claude discover tools on demand instead of loading every definition into context upfront.

In the Tool Search design, you still provide all your tool definitions to the API, but you mark most of them with defer_loading: true. Deferred tools are not initially loaded into Claude’s context. At the beginning of a conversation, Claude sees only:

-

The Tool Search Tool itself (for example,

tool_search_tool_regex_20251119ortool_search_tool_bm25_20251119). -

Any tools with

defer_loading: falsethat you want to keep always available (for example, a core search tool used on nearly every task).

When Claude needs specific capabilities, it calls the Tool Search Tool. That tool queries the full tool catalog—names, descriptions, argument names, and descriptions—and returns a handful of tool_reference blocks corresponding to the most relevant tools. The runtime then expands those references into complete tool definitions inside Claude’s context. From that point on, Claude calls those tools as usual.

Under the hood there are two search variants:

-

A regex flavor, where Claude emits Python-style regular expressions such as

"github.*pull"to match tool names and descriptions. -

A BM25 flavor, where Claude issues natural language queries such as “create a GitHub pull request,” and the search engine ranks tools based on textual relevance.

In both cases the crucial property is that the index of tools lives outside the LLM’s context. The model pays the token cost for:

-

The search tool itself, which is small, and

-

Only the subset of tool definitions it actually pulls in during the task.

Anthropic reports that this “defer + search” pattern reduces tool-definition token usage by roughly 85% on MCP-heavy workloads, while also improving tool selection accuracy. In their internal evaluations, Opus 4’s performance on a large MCP benchmark improved from 49% to 74%, and Opus 4.5 from 79.5% to 88.1%, when Tool Search Tool was enabled.

For MCP in particular, Anthropic’s examples show a useful pattern. You can define an mcp_toolset with a default configuration of {"defer_loading": true} so that all tools from that server are deferred by default. You then override a few high-use tools to stay always loaded. Tool Search then becomes a unified discovery layer across all your MCP servers: Claude starts each conversation knowing only about the search tool and a small core, and pulls in specific MCP tools only when it needs them. Because most tools never appear in the initial prompt, this approach also works well with Anthropic’s prompt caching: your base system prompt and core tools remain cacheable, while deferred tools are added only when required.

The net effect is that your full tool library remains available, but you only pay the token cost for tools that matter to the current task.

Programmatic Tool Calling: Claude writes the orchestrator

The second Anthropic feature, Programmatic Tool Calling, tackles the other half of the problem: not just which tools are visible, but how tool calls are orchestrated.

In traditional tool calling, Claude calls one tool at a time, receives the full result into its context, and decides what to do next. Each step is another model invocation, and every intermediate dataset flows through the context window, whether it is truly needed or not.

With Programmatic Tool Calling, Claude instead writes a Python program that orchestrates the entire workflow. That program is executed inside a Code Execution tool, and it is the program—not the model—that calls your tools, processes their outputs, and decides what data should be passed back into the LLM.

In concrete terms:

-

You opt specific tools into this mode using an

allowed_callersfield. Tools marked with"allowed_callers": ["code_execution_20250825"]are exposed as Python functions in the sandbox container. -

Claude’s first step is to emit a

code_executiontool call whose input is an orchestration script. That script might, for example, fetch team members, pull their expenses in parallel, compute totals, and filter for the people who exceeded their travel budget. -

The runtime runs that script in the container. Whenever the script calls one of your tools, execution pauses and the API sends you a

tool_useblock tagged as coming fromcode_execution. You return atool_result, the script resumes, and all intermediate values stay inside the container instead of in Claude’s context. -

When the script finishes, it returns a compact result (for example, a small JSON list) to the model, which then produces the final answer for the user.

Anthropic’s own blog illustrates this with a “who exceeded their Q3 travel budget?” example. In the traditional flow, thousands of expense line items and budget records are streamed into Claude’s context and multiple inference passes are needed. With Programmatic Tool Calling, Claude writes a short asynchronous Python script that fetches all the data, computes totals, and emits only the handful of employees who are over budget. Only that final, distilled JSON response enters the model’s context. Anthropic reports around 37% token reductions on complex tasks by keeping intermediate data out of the window, along with latency improvements because you no longer perform a full model call after every tool invocation.

Conceptually, this is more than a minor API optimization. It turns the agent into a disposable backend: Claude uses its reasoning once to write a task-specific microservice in Python, then the heavy lifting—loops, branching, parallel calls, joins, aggregation, error handling—runs entirely in code. The model is sampled once to generate the orchestrator and once to consume the final result; everything in between happens in the sandbox, not in the LLM’s context window.

Programmatic Tool Calling is most beneficial when:

-

You are processing large datasets but only care about aggregates or summaries.

-

The workflow involves several dependent tool calls and non-trivial logic.

-

You want to filter, sort, or transform tool results before they can influence the model’s reasoning.

-

You need to ensure that intermediate data does not bias the model in unintended ways.

-

You have many similar operations to run in parallel, such as checking dozens of endpoints or repositories.

Why these features go beyond classic tool calling

Taken together, Tool Search Tool and Programmatic Tool Calling attack both major sources of tool-related token bloat:

-

Tool availability is treated as a retrieval problem. The model no longer carries hundreds of tool schemas in its context; it uses the Tool Search Tool to retrieve a small working set of tools per task.

-

Orchestration is expressed as code instead of as a long chain of conversational tool calls. Intermediate data stays in the execution environment rather than inflating the LLM’s context window.

In other ecosystems you can approximate pieces of this with caching, multi-agent design, and custom orchestrators, but Anthropic’s approach integrates these patterns directly into the platform and its MCP story. For organizations leaning heavily on MCP and complex toolchains, this sets a high baseline for what “efficient agentic systems” can look like.

OpenAI: Responses API and Agents SDK

OpenAI also invests heavily in reducing the friction and cost of tool usage, but approaches the problem from a slightly different angle. Their tools focus on ergonomics, scope control, and caching rather than on shifting orchestration into code that the model writes once and then hands off.

Responses API with hosted MCP

OpenAI’s primary answer to “too much MCP metadata in the prompt” is the Responses API with hosted MCP support.

Instead of serializing every MCP tool definition into each request yourself, you configure an MCP connection once—server label, URL, and an allow-list of which tools the model should be able to call. The platform then handles listing tools and invoking them behind the scenes. This means you are not constantly shipping large JSON schemas through your own infrastructure or over the network.

Internally, OpenAI caches tool lists for the duration of a conversation, so it does not need to re-query the MCP server on every call. Combined with prompt caching, the large, stable prefix that contains system instructions and tool definitions becomes much cheaper and faster to reuse across calls. The tokens still exist logically, but you are no longer paying full price for them each time.

In practice this shifts cost and complexity away from your application. You send a compact configuration; the Responses runtime handles MCP plumbing, tool discovery, and multi-step tool usage inside a single call. This improves network efficiency and developer experience, even though the model still has to “see” the tools it might call.

Agents SDK with MCP: scoping and caching

On top of the Responses API, the OpenAI Agents SDK provides a higher-level framework that pushes optimization a step further by making it easy to control which tools are visible to the model on each run.

Each agent in the SDK can have its own toolset, and tools can be conditionally enabled or disabled at runtime. Disabled tools are completely invisible to the model; their descriptions and schemas do not occupy any context tokens for that call. This encourages you to create specialized agents focused on narrower domains.

For MCP servers, the Agents SDK adds tool filtering and tool-list caching. You can filter a server’s tools down to the subset that makes sense for a particular agent or task instead of exposing the entire catalog at once. At the same time, list_tools results are cached by the SDK, so you are not repeatedly pulling and parsing the full registry on every run.

The SDK also separates data that the model must see from data only your code needs. Heavy payloads, connection details, and other state live in a local run context and are accessed through tools rather than being inlined into the prompt. The practical outcome is that your model input is dominated by a small, curated tool subset and relevant data, not by raw MCP metadata and large payloads.

What is still missing relative to Anthropic

The main differences compared with Anthropic’s newer features are about who orchestrates workflows and how tool metadata is loaded.

Anthropic’s Programmatic Tool Calling changes the execution model by having Claude emit a Python program that coordinates many tool calls. Most intermediate results are processed entirely in code without re-involving the model. Large tool registries can stay outside the prompt and be loaded on demand through Tool Search.

OpenAI does not currently expose a dedicated feature where the model writes a long-lived program that then orchestrates tools largely without re-invoking the model. Nor does it provide a first-class, named mechanism for deferring tool loading so that a massive global tool universe starts entirely outside the context window and is pulled in only when needed. The core pattern remains familiar: the model is presented with a set of tools, it chooses among them, and tool results come back as messages that become part of the conversation history.

So, as of early December 2025, the fair summary is that OpenAI partially addresses the tool-metadata problem rather than eliminating it. Hosted MCP, Responses, and the Agents SDK deliver better ergonomics, caching, and powerful ways to narrow the visible tool set per agent and per run. If you are managing very large MCP catalogs, you will still need to architect around the problem yourself with careful tool scoping, multi-agent designs, and MCP-side filtering, rather than relying on a single Programmatic Tool Calling–style mechanism.

Google / Gemini: MCP, ADK, and Context Caching

Google’s Gemini stack tells a broadly similar story to OpenAI’s: MCP is treated as a first-class integration point, there is support for tool filtering, and there are robust context caching mechanisms for instructions and tools. What you do not get yet is a named equivalent to Anthropic’s Programmatic Tool Calling; instead you combine built-in features with ADK patterns to reach similar outcomes.

Gemini API: MCP and caching at the model layer

At the model level, the Gemini API gives you function calling and tools, plus MCP support in the official SDKs.

With Python or JavaScript/TypeScript, you can wrap a running MCP client (for example, using ClientSession and mcpToTool(client)) and pass it into the tools configuration for a generateContent call. The SDK handles the tool loop: Gemini decides to call an MCP tool, the SDK executes it, feeds the result back, and continues until the model stops requesting tool calls. This is similar in spirit to OpenAI’s hosted MCP, where you treat an MCP server as a logical toolset and let the runtime manage list_tools and call_tool interactions.

Google’s documentation is explicit about tool-set sizing. Function descriptions and parameters count toward your input tokens, and you are encouraged to keep only relevant tools active per request, ideally on the order of 10–20 functions. If you hit token limits, the recommended remedies are to trim function descriptions and reduce the number of tools or use dynamic selection. The guidance is clear: do not dump your entire MCP universe into every Gemini request.

On the “stop re-sending giant schemas” side, Gemini offers Context Caching as a first-class feature. You can push large prompt segments—system instructions, shared context, and tool schemas—into a cache and reuse them by reference in subsequent calls. Cached content is treated as a prefix to the prompt, which means you avoid re-uploading it and you pay a discounted rate for cached tokens. On Vertex AI, cached tokens are billed at a significant discount (around 90%) and also provide latency improvements, with both implicit (automatic) and explicit caching modes available.

So at the Gemini API level you get automatic MCP tool usage, guidance to keep the active tool set small, and a way to cache large, stable prompt segments so you are not constantly re-sending them. This does not remove tool metadata from the model’s context, but it directly addresses cost and bandwidth, and encourages scoped tool lists.

ADK and Vertex AI Agent Builder: MCP toolsets and context management

More sophisticated optimizations appear one layer higher, in the Agent Development Kit (ADK) and Vertex AI Agent Builder.

ADK is Google’s open-source toolkit for building agents and multi-agent systems on top of Gemini and Vertex. It treats MCP as a first-class tool type. Vertex AI Agent Builder then uses ADK as the construction layer and provides a managed runtime with an Agent Engine, sessions, memory, monitoring, and a tool catalog that includes MCP-based tools.

Within ADK, the key abstraction for MCP is McpToolset. You configure it with connectivity details for the MCP server (stdio or SSE/HTTP), and it:

-

Connects to the server.

-

Calls

list_tools. -

Converts discovered MCP tools into ADK

BaseToolinstances. -

Exposes those tools to your

LlmAgent. -

Proxies

call_toolrequests back to the MCP server.

Critically, McpToolset supports a tool_filter parameter. This lets you select a subset of tools from an MCP server instead of exposing everything to the agent. Combined with ADK’s patterns for multi-tool agents and teams of agents, the intended design is to partition a large MCP catalog across specialized agents, each with a relatively narrow tool list.

ADK also integrates Context Caching with Gemini via its App abstraction. You configure a ContextCacheConfig with thresholds such as minimum token count, time-to-live, and maximum reuse count. The framework then uses Gemini or Vertex context caching beneath the surface to cache repeated request segments for all agents in the app. ADK’s API reference notes that explicit cache entries can be created not only for user content but also for instructions, tools, and other large repeated chunks. In practice this means you can cache:

-

Static system prompts.

-

Large function and tool schemas.

-

Shared data segments used across runs.

Finally, ADK provides a broader “context management” story: context caching, context compression, sessions, and memory are separate components that you can combine. While this is not MCP-specific, it is an important part of keeping context under control in multi-tool, multi-step setups. Stable content can be cached, older state can be compressed, and only the relevant slice of history is kept in front of the model.

Comparison with Anthropic’s approach

Seen from the angle of “my MCP server has a large number of tools and I do not want to send every schema in every call,” Google’s Gemini stack offers building blocks similar to OpenAI’s:

-

A way to treat an MCP server as a single logical tool bundle (

mcpToToolin the SDKs, orMcpToolsetin ADK) rather than manually serializing each tool. -

Filtering controls (

tool_filterand per-agent tool lists) so each agent only exposes a manageable subset of tools at inference time. -

Context caching so long-lived, stable prompt segments—including instructions and tool definitions—are reused at a discounted rate, which makes “big tool metadata” cheaper and less repetitive.

What Gemini does not currently provide is a named, Anthropic-style Programmatic Tool Calling feature where the model emits a long-lived program that then orchestrates tools largely without re-invoking the model. You can build patterns like that yourself on top of Gemini—for example, CodeAct-style agents that generate code or workflows that talk directly to MCP servers—but those are design patterns you implement on top of ADK, not a dedicated API surface.

As a result, if you are integrating MCP with Gemini and want to minimize context pressure from tool metadata, the practical recipe today is to:

-

Use ADK and

McpToolset, and aggressively scope each agent’s tools usingtool_filter. -

Architect around multiple specialized agents instead of a single “god agent” that sees everything.

-

Enable context caching (Gemini/Vertex plus ADK’s

context_cache_config) for static instructions, MCP tool schemas, and other large, repeated content.

That combination does not magically hide MCP tools from the context window, but it allows you to avoid resending large schemas on every call, reduce their cost substantially, and ensure each LLM invocation sees only a curated slice of your MCP universe.

Practical Design Considerations for Startups

From a distance, these platform features can feel abstract. For a startup founder, CTO, or technical leader, the more useful question is: how should we design our agentic systems today, given what these vendors support?

A few patterns emerge across Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google.

First, resist the temptation to build a single all-knowing agent that has access to every tool in the company. It is almost always better to organize tools into focused domains—support, finance, infrastructure, analytics, operations—and give each agent only what it needs. This improves reasoning quality, reduces context size, and simplifies security boundaries.

Second, treat tool metadata as infrastructure, not as part of every prompt. Wherever your platform allows it, push tool definitions and schemas into a cache or index, then load only what is needed per run. Anthropic’s Tool Search Tool does this explicitly; OpenAI and Google do it partially through hosted MCP, tools-as-config, and context caching. In all three cases, the design principle is similar: keep the model’s working set small.

Third, move orchestration as close to code as your platform allows. With Anthropic’s Programmatic Tool Calling you can push most of the logic into a one-off Python script that Claude writes and executes in a sandbox. With OpenAI and Gemini you can approximate the same idea by letting the model generate code or workflows that run between model calls. In all cases, the goal is to avoid forcing the LLM to “watch” every intermediate result and to minimize the number of full inferences in a workflow.

Finally, measure token usage at the level of individual workflows, not just at the account level. When you can see how many tokens are being spent on static metadata, tool outputs, and actual business content, you can decide where it is worth investing in refactoring, caching, or vendor-specific features. In future posts in this series, we will walk through concrete measurement setups and cost models you can plug into your own systems.

Summary

Benefits of token-efficient MCP tool integration

Across vendors, the optimizations described in this article target the same underlying issue: unbounded tool metadata and naïve orchestration lead to bloated context windows, higher costs, and reduced accuracy. By redesigning how tools are exposed and how workflows are orchestrated, you can:

- Reduce token usage by treating tools as an index and loading only a small working set per task, and by keeping intermediate data in code rather than in the model’s context.

- Improve accuracy because models select among fewer tools at a time and are less likely to be confused by overly large toolsets and irrelevant intermediate data.

- Lower latency and infrastructure load by cutting down on the number of full model calls in multi-step workflows and by caching large, stable prompt segments.

- Increase robustness and control by expressing orchestration logic in explicit code, with clear loops, conditionals, and error handling, instead of relying solely on the model’s internal reasoning and conversational history.

For organizations building serious agentic systems on top of MCP, these are no longer micro-optimizations. They determine whether your AI-based workflows can scale economically and remain debuggable and reliable as you expand your tool surface.

Anthropic vs OpenAI vs Google: current trade-offs

At a high level, all three vendors recognize the same pain points and offer overlapping building blocks, but with different emphases.

Anthropic currently provides the most integrated approach for MCP-heavy environments:

-

Tool Search Tool treats a large tool library as a searchable index. Most tools are marked with

defer_loading: true, and Claude discovers and loads only what it needs during a task. This can reduce tool-definition tokens by around 85% and improves tool selection accuracy, especially when many MCP servers and tools are involved. -

Programmatic Tool Calling shifts orchestration into Python code that Claude writes once and runs in a sandbox. Intermediate tool outputs stay in code, and only a distilled result returns to the model, yielding meaningful token and latency savings.

Together, these features effectively redefine how MCP tools interact with the context window: tools are discovered on demand, and workflows are executed primarily in code.

OpenAI’s approach focuses on hosted infrastructure and flexible scoping:

-

Responses API with hosted MCP moves MCP plumbing into the platform. You configure an MCP connection once, and the runtime handles listing and invoking tools, with tool lists cached per conversation and combined with prompt caching.

-

Agents SDK gives you per-agent toolsets, conditional enabling and disabling of tools, MCP tool filtering, and local run context for heavy state. This encourages narrower agents and keeps the visible toolset small for each run.

OpenAI partially mitigates tool-metadata overhead but still relies on the traditional pattern where the model sees its tools and each tool call flows back through the conversation. Programmatic orchestration and deferred tool loading are patterns you implement yourself, not named features.

Google’s Gemini stack sits in a similar space to OpenAI, with strong emphasis on context management and multi-agent design:

-

Gemini API supports tools and MCP integration in the SDKs, with clear guidance to keep only 10–20 relevant tools active per request. Context Caching lets you reuse large prompt segments, including tool definitions, at a discounted token cost.

-

ADK and Vertex AI Agent Builder introduce

McpToolsetfor discovering and exposing MCP tools,tool_filterfor scoping toolsets, and app-level context caching for instructions, schemas, and shared content. Additional components for compression, sessions, and memory help keep long-running context under control.

Gemini does not ship a dedicated Programmatic Tool Calling feature, but ADK gives you enough primitives to build similar code-driven orchestration patterns yourself if you choose.

Choosing a direction

For a startup or mid-sized organization, the choice between these approaches is ultimately a strategic one.

If you are heavily invested in MCP, expect very large tool catalogs, and want a platform that directly addresses both tool discovery and orchestration cost, Anthropic’s combination of Tool Search Tool and Programmatic Tool Calling currently offers the most direct path to aggressive token savings and higher tool accuracy out of the box.

If you prioritize hosted infrastructure, flexible multi-agent design, and are comfortable building more of your own orchestration and indexing layers, OpenAI’s Responses, hosted MCP, and Agents SDK give you strong primitives for scoping and caching, and a broad ecosystem to build on.

If you are already on Google Cloud or want deeper integration with existing data and ML infrastructure, Gemini plus ADK and Vertex AI Agent Builder provide first-class MCP support, robust context caching, and a well-structured way to build teams of agents with carefully scoped toolsets, even though you may need to implement more of the orchestration patterns yourself.

In all three ecosystems, the trajectory is clear: tools are moving out of the static prompt and into more dynamic, indexed, and code-driven architectures. For founders, technical leaders, and investors, the important takeaway is that token usage by MCP tools is both a cost center and an opportunity. Designing with these newer approaches in mind can make the difference between agents that look impressive in demos and agents that you can operate efficiently and reliably at scale.