LLMs as the Next Abstraction Layer: A Compiler for Human Intent

LLMs as the Next Abstraction Layer: A “Compiler” for Intent

When people say “LLMs write code,” the conversation often falls into two unhelpful extremes: hype (“software is solved”) or denial (“this is just fancy autocomplete”). Neither describes what’s actually changing.

A more useful framing is this: LLMs - often delivered through AI agents - add a new layer to the translation stack that sits between human intent and machine execution. They don’t replace compilers, transpilers, interpreters, runtimes, or programming languages. They sit above them, translating higher-level intent (often expressed in plain English) into the code artifacts we already know how to verify, build, ship, and operate.

The analogy isn’t literal. Traditional compilers operate on formal languages with strict syntax and defined semantics. They’re deterministic systems with well-understood failure modes. LLMs are probabilistic and non-deterministic. Still, as a mental model, “LLMs as a probabilistic compiler for intent → source code” is clarifying - especially if you’ve watched software advance by steadily climbing abstraction ladders.

The story of programming is the story of translation

From the beginning, programming has been about translation: turning a human idea into machine behavior.

Early computing required translation that was literal and unforgiving. Instructions were entered through whatever mechanisms the machine supported - switches, paper tape, cards - because that’s how you communicated with hardware. The real constraint wasn’t the input medium; it was the abstraction level. The machine’s “native language” was low-level, and humans had to meet it there.

The first major productivity unlock arrived when we stopped writing raw machine instructions and began writing symbols for them: assembly language. It didn’t change what the CPU could do, but it dramatically changed what humans could manage - making larger programs feasible without drowning in opcodes and addresses.

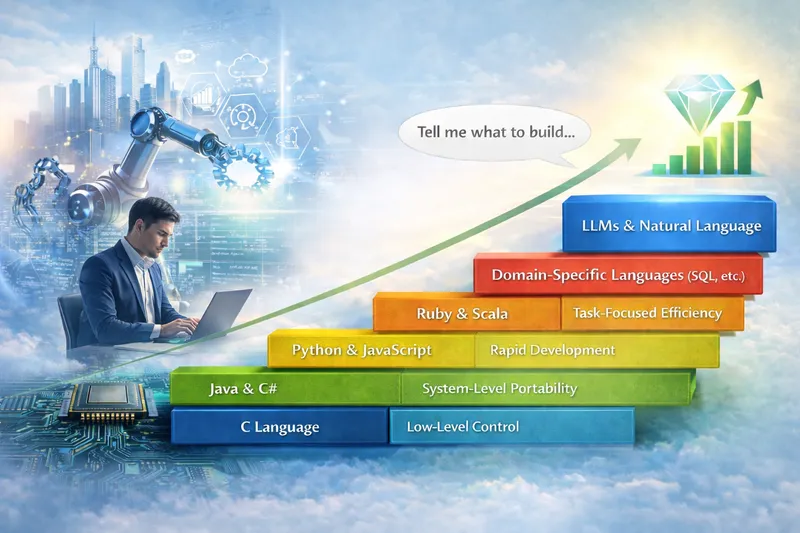

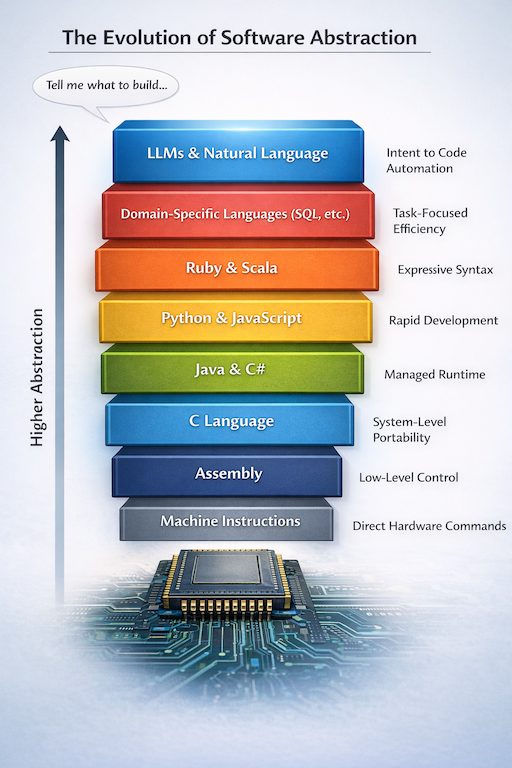

From there, the same pattern repeated: raise the level of expression, and you can build more complex systems with the same cognitive budget.

C and C++ weren’t successful because they looked like English. They won because they made systems portable and scalable while staying close enough to the machine to remain practical. Later, managed runtimes and higher-level languages automated entire categories of concerns - memory management, safety checks, portability, and rich standard libraries. Java and C# popularized a clean pipeline: write readable code, compile to an intermediate representation, and let a runtime optimize execution.

Python and JavaScript pushed productivity even further by prioritizing iteration speed and ecosystem leverage, then delegating performance to interpreters and JIT compilers. In parallel, engineers kept building “mini languages” whenever general-purpose languages felt too limiting. DSLs are the clearest proof of that impulse, and SQL is the canonical example: describe what you want, and the engine figures out how to execute it.

General-purpose languages also evolved toward greater expressiveness - Ruby’s readability, Scala’s hybrid power, and functional ideas that emphasize composition and declarative reasoning.

All of this reflects one direction of travel: humans move “up,” and machines take on more translation work. LLMs aren’t a break from that pattern. They continue it - just with a bigger leap in the input layer by making natural language a practical on-ramp into software creation.

A rough abstraction ladder (not a strict timeline): machine instructions → assembly → compiled languages (C/C++) → managed runtimes (Java/C#) → dynamic languages (Python/JavaScript, Ruby) → DSLs (SQL, etc.) → natural-language intent.

What changes when the input is natural language

If you’ve used an AI agent to implement a feature, you’ve already felt the shift. You can describe what you want the way you’d describe it to a teammate: desired outcomes, constraints, examples, failure modes, and edge-case behavior. The model turns that into code, then your build, tests, and runtime either validate it - or reject it.

That’s why the compiler analogy is tempting: it feels like compilation. You start with intent and end with something executable - just faster, and with fewer “translation steps” performed manually.

The key distinction is where meaning comes from. A traditional compiler translates a formal language with explicit rules and defined semantics. An LLM translates underspecified intent expressed in a natural language that is inherently ambiguous. That ambiguity isn’t a flaw in the tool so much as a truth about the work: many software tasks begin ambiguous, and teams spend significant time clarifying intent before anyone writes “real code.”

For decades, we treated that layer - tickets, docs, design notes, chat threads, PR descriptions - as fundamentally un-compilable. We wrote it down and then manually translated it into code. LLMs are the first broadly useful tool that can operate directly on that layer and produce plausible implementations.

Importantly, LLMs also shift where strictness lives. Instead of forcing humans to speak rigid syntax up front, the model produces artifacts that are then forced through rigid gates: type checkers, compilers, linters, unit tests, integration tests, security scanners, deployment pipelines, and runtime behavior. The “formalization” often happens later in the chain, not earlier.

That changes the feel of programming - and it changes the bottleneck.

As abstraction rises, verification becomes the bottleneck

There’s a near-universal rule in software: whenever we raise the abstraction level, the work shifts from “how do I express this?” to “how do I know it’s correct?”

Assembly made programs easier to express, but correctness relied heavily on debugging discipline. Higher-level languages made intent easier to express, and correctness leaned more on type systems, tooling, tests, and conventions. Managed runtimes removed entire classes of memory bugs, but correctness and performance then depended on understanding runtime behavior and building the right guardrails. SQL abstracted away execution planning, but correctness and performance shifted to schema design, indexing, and knowing how the optimizer behaves.

LLMs intensify this pattern. They drastically reduce the cost of producing code-shaped output, but they don’t magically produce correctness. They generate candidates - often strong ones, sometimes subtly wrong ones that look plausible and can pass casual review. That’s not a moral failing of the tool; it’s what happens when you translate ambiguous intent by inference.

This is why the winning workflow isn’t “ask for code.” It’s “state behavior, generate artifacts, verify aggressively, iterate quickly.” LLMs don’t remove engineering rigor; they reward it.

A codebase with strong tests, clear architecture, clean interfaces, and good observability behaves like a well-designed target: it gives sharp feedback when something is wrong. In that environment, probabilistic synthesis becomes a force multiplier - the model proposes, the system evaluates, and the loop tightens.

Seen this way, the “LLMs as a compiler layer” framing becomes more than metaphor. It becomes a practical design principle: to benefit from a probabilistic front-end, you need deterministic back-ends and strong verification gates.

The new stack looks different than the old one

The traditional mental model was simple: write source code → compile/interpret → run.

The emerging model looks more like this: express intent → the LLM proposes coordinated changes across a codebase → automated checks reject what doesn’t work → revisions continue until the change satisfies constraints → the system ships and is observed → feedback further constrains behavior.

The subtle shift is the unit of work. It’s no longer “a file” or “a function.” It’s a change that satisfies constraints. The model isn’t merely producing snippets; it’s participating in an iterative loop that resembles real development: propose, run, fix, refine.

This is also why declarative systems are useful anchors. SQL didn’t remove the need for database expertise; it moved expertise upstream into schema design and correctness/performance guardrails. LLM-assisted development does something similar across a wider territory: it reduces the friction of translating intent into code and shifts value toward constraints, architecture, and verification.

What this means in practice

When code generation becomes fast, iteration loops tighten. Faster iteration means faster learning, and faster learning compounds - better product fit, quicker integration, smarter sequencing, and more leverage per engineer-hour.

The organizations that benefit most aren’t necessarily the loudest adopters. They’re the ones that can safely absorb the speed - by making behavior explicit, keeping feedback loops tight, and treating verification as a first-class asset.

A reframing for the cautious and skeptical

Skepticism is healthy. Software has a long history of tools that promised productivity and delivered complexity. Caution is earned.

But two separate claims often get tangled. One is that AI is perfect and replaces judgment - false, and dangerous to believe. The other is that AI represents a new abstraction layer that performs translation work we used to do manually - very often true in practice. Intent becomes code faster, iteration becomes cheaper, and verification becomes the center of gravity.

If you accept the second claim, the conclusion isn’t that people don’t matter. It’s almost the opposite:

The craft moves upward.

The durable skills remain the same ones that have always separated excellent builders: clarity of thought, decomposition, constraint design, architectural taste, and the habit of verifying reality rather than trusting appearances.

In that sense, treating LLMs - and the broader agent-driven toolset - as a probabilistic intent → code “compiler” isn’t an insult to the discipline. It’s a description of where the discipline is heading: less time spent on mechanical translation, more time spent on intent and correctness.

And that’s exactly what every prior abstraction jump has done - just at a higher level than we’ve seen before.